And, with millions still unemployed and hundreds of millions still suffering the economic after-effects of the last crisis, we're just about due for the next one. That's why we convened a panel at last weekend's Netroots Nation conference titled "Stopping the Next Depression: Ending Too Big to Fail." And that's why our first question was, "What would happen if the 40 million people who live in underwater American homes went on a mortgage strike?"

The panelists included Sen. Jeff Merkley, D-OR; Phil Angelides, former California State Treasurer, gubernatorial candidate, and Chair of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission; author Robert Kuttner (Debtors' Prison); and professor/author Anat Admati (The Bankers' New Clothes).

Here are some of the key points we addressed:

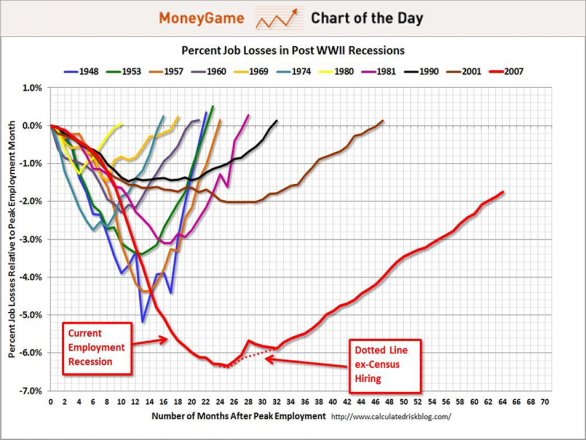

The jobs crisis created by the 2008 crisis is much deeper and long-lasting than that caused by any recession since the Great Depression of the 1980s. (See Figure 1, below.)

The total economic loss from 2008 crisis is roughly the same as that we experienced during the Great Depression, but stretched out over a longer period of time. (See "The Long Depression.")

Without proper regulatory protections, we're likely to see recessions re-occurring every five to seven, or seven to ten, years. JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon even bragged about it, saying in 2010:

"It's not a surprise that we know we have crises every five or 10 years. My daughter came home from school one day and said, 'Daddy, what's a financial crisis?' And without trying to be funny, I said, 'it's the type of thing that happens every five, 10, seven, years.' And she said: 'Why is everybody so surprised?'"Dimon later said, "This bank is anti-fragile. We actually benefit from downturns." In other words, misery is their business model.

Recessionary cycles have more or less tended to follow the "Dimon's daughter" pattern during periods of regulatory underenforcement, which is what we have now. That means the next recession could come along at any time. With mega-banks even bigger than they were before, and with so much economic damage and fragility left over from the last crisis, the next recession could lead to a major worldwide depression.

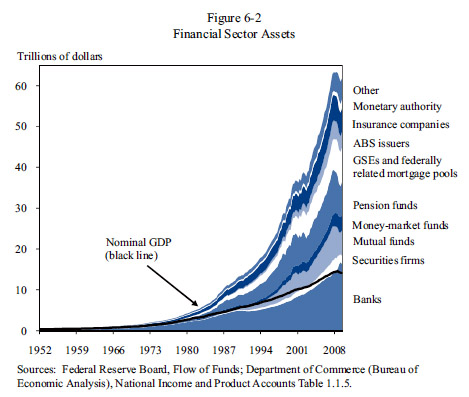

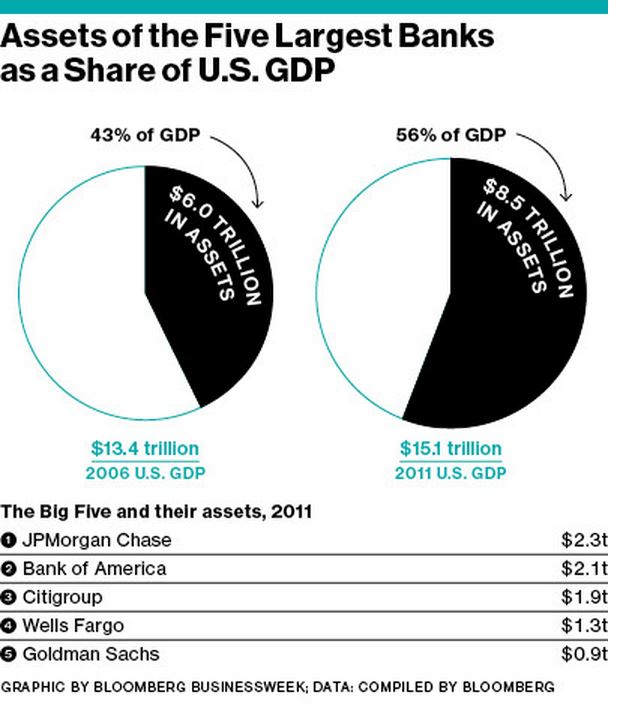

The financial sector had exploded in size before the last crisis, sucking all the oxygen out of the economy by diverting profits into nonproductive financial speculation. (See Figure 2, below.) After the 2008 crisis it promptly began expanding again. And Too Big to Fail became an even bigger problem: Assets at the top five U.S. banks now exceed half the Gross Domestic Product of the entire country, up from 42 percent. (See Figure 3.) That growth was spurred in part by mergers conducted with the government's approval -- or even at its insistence.

There is still an enormous amount of outstanding derivatives risk, and markets for several over-the-counter (OTC) securities are even more concentrated than they were before the 2008 crisis. (Slides that cover those last two points, and several of those which follow, are included in the PowerPoint presentation embedded at the bottom of this post.)

The bankers who inflated the real estate market in the run-up to the crisis are up to their old tricks, using their old tools. Dead economic ideas have risen from the grave to threaten us again, thanks in large part to the systemically corrupt relationship between money and political power.

What's Washington doing about it? Republicans are working feverishly to neutralize the already-weak Dodd/Frank reform act, while the Obama Justice Department's shameful lack of prosecutions has given bankers free rein to continue defrauding customers (see David Dayen's piece on Bank of America) and laying the groundwork for future economic disasters.

We ran out of time for questions during the panel, in part because we on the panel talked for a long time. It was exacerbated by a couple longish questions, including one which I thought haranguing Sen. Merkley a little unfairly.

(As an aside, "Q&A time" at these events is always heavier on the "A" than the "Q." Occasionally a questioner may act as if they were on some inverted version of Jeopardy!, where "your questions must be phrased in the form of an answer" rather than vice versa. You know what I mean...)

Here are the questions I would've liked to ask the panel, if we had found the time:

Why are bankers treated as economic experts? Reporters and politicians are still asking their opinions, which encourages them to engage in self-serving political stunts like "Fix the Debt." It's like going to the captain of the Exxon Valdez for advice on navigation. They shouldn't even be treated as banking experts, much less as economic ones.

How do we explain to the public that top bankers are actually quite unimpressive and have underperformed both managerially and economically?

How do we educate decision-makers and influence leaders? Anat Admati and her co-author wrote in The Bankers' New Clothes: "In trying to engage with policymakers and others on the issues, we discovered that many of them had no interest in engaging in the issues - not because of what they knew or did not know but because of what they wanted to know."

Or, I would assume, what they wanted not to know. How do we address this problem among a) economists, b) politicians, and c) journalists and pundits?

Can the Fed do more? Should it step outside its traditional role to do so?

If you could tell the average American one thing she or he doesn't know about America's big banks, what would it be?

What is one government response to the financial crisis which you simply -- and naively -- assumed would be done and hasn't been done?

How great a danger does shadow banking pose? How can it be controlled?

What's the right amount of allowable leverage?

How can we generate a shift in general or cultural perception, so that people understand we don't have to submit to unjust banking behavior or tolerate too-big-to-fail banks? And, in a related question:

How can we implement a "culture of shame" against bankers behaving badly?

I'm sure you'll have some questions of your own after watching the video. Here are some figures, pulled from my slide presentation (which is at the bottom of this page).

Figure 1: Jobs lost since onset of recession

Figure 2: Growth in financial sector

Figure 3: Bank size as percent of GDP

Its coming and no one is watching again

Its coming again, will investors be smart this time and bail out? No one is watching, why?

ReplyDelete